Tired of your camera deciding everything for you? Let’s unlock its full potential today!

Here is the answery bit

Ever wonder why your camera sometimes nails the shot in Auto, yet other times your brilliant photographic idea falls flat? It’s all about how much control you have, and how much you let the camera decide. Your camera’s shooting modes are your direct gateway to greater creative expression. They bridge the gap between simply snapping a picture and intentionally crafting an image that reflects your vision.

Moving beyond Auto, whatever it is called, allows you to tell the camera what’s genuinely important to you – whether that’s freezing action, blurring a background, or taking complete, meticulous command of the light. Each mode offers a distinct balance of automation and your input, designed to help you achieve specific photographic results without getting bogged down in every single setting.

Auto modes are convenient and great for beginners, and for folk who can’t be bothered to use other modes. And if that is you and you are happy with this then that is of course fine. But, for specific creative or precise technical results, you must explore other modes. Auto decides everything, often sacrificing your creative vision for a “safe” exposure. This can lead to unpredictable results and limits your ability to do stuff like intentionally blur backgrounds, emphasise fine details, create motion blur, take long exposures, and of course let’s not forget to manage tricky lighting. Sticking to Auto also stops you from truly understanding how light, aperture, shutter speed, and ISO interact. More aperture and shutter speed for me, but I will come onto that lot later.

Understanding these modes means you can stop guessing and start creating with purpose, which will result in you creating better photos.

Other than full auto, program, manual, aperture priority and shutter priority modes there are lots of scene specific modes. I am not talking about those here. I am talking about the scene specific ones, like landscape, portrait, HDR, backlit night portrait, rabbit in the headlights in a snow storm, that kind of thing. All sorts of scene specific stuff. I am not talking about those for one reason and one reason only. I have not used any of them in decades. If ever. Blimey that was a tad dramatic!

Hello and welcome to the Photography Explained Podcast! And a very good morning, good afternoon, or good evening to you, wherever you are in the world. I’m your host, Rick, and in each episode, I try to explain one photographic thing in plain English in less than 27 minutes (ish), without the irrelevant details. I’m a professionally qualified photographer based in England with a lifetime of photographic experience, which I share with you in my podcast.

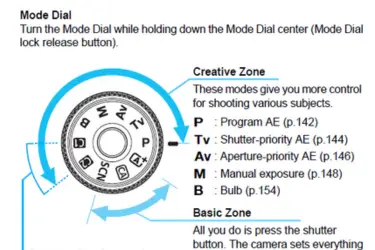

Today, we’re diving into the heart of your camera’s control – its shooting modes. That dial on top of your camera with letters like M, Av, Tv, P, and that green square? And lots of symbols. We’ll break down exactly what each mode means, when to use it, and how understanding them gives you immense creative power over your photos. This isn’t about complex theory; it’s about practical use to get the shots you want, every time.

How utterly splendid. Let’s get into this.

Here are 5 top tips for Understanding and Using Your Camera Modes!

OK. Time for some detailed photography tips to help us consistently choose the right mode for the right photo. These strategies will simplify your camera dial and help you achieve professional results.

1: Auto Mode: The Green Square Explained (Your Camera’s Basic Brain)

First up, let’s talk about Auto Mode. This is usually marked with a green square or simply “Auto” on your camera’s dial. Here, your camera makes every single decision for you: aperture, shutter speed, ISO, flash, even white balance. It’s designed to give you a “correctly exposed” image without your input.

When to use it:

- Quick snapshots: When you just need to capture a moment without thinking. Like when your dog does something unexpectedly cute.

- Handing off your camera: If you give your camera to a non-photographer to take your picture, Auto mode is their friend.

- Unexpected moments: When a scene unfolds quickly, and there’s no time to fuss with settings.

- If you are an absolute beginner.

- Or if you just can’t be bothered using anything else!

The downside: You have no creative control. The camera aims for a technically correct exposure, but it might not be the best for your artistic intent. For instance, it might use high ISO in good light, giving you unwanted noise, or a wide aperture that blurs out too much. Think of Auto as training wheels. Great for getting started, but you’ll soon outgrow them.

Right – next.

2: Program Mode (P): The Intelligent Auto (Your Camera’s Smart Assistant)

Our next mode is Program Mode, often marked with a “P” on your dial. No that is not P for professional! This is like an “intelligent auto,” a very useful stepping stone. Your camera still chooses both aperture and shutter speed for correct exposure, but it gives you control over other important settings like ISO, flash, and white balance. Crucially, in Program mode, you can often “shift” the program – meaning you can rotate a dial to choose different combinations of aperture and shutter speed that still result in the same exposure.

When to use it:

- Faster workflow: When you need a quick, reliable exposure but want to manage things like ISO to control noise, or to force the flash on or off.

- Learning exposure combinations: It’s a great way to see how aperture and shutter speed relate – as you change one, the camera automatically changes the other to maintain exposure.

- General shooting: A fantastic default for everyday photography when you want more control than Auto but less manual intervention.

Program mode is a significant step up, offering plenty of flexibility without requiring you to set everything yourself.

Tip 3: Aperture Priority Mode (A or Av): Master Your Depth of Field (Control the Blur!)

Host: Now we’re truly getting into the creative modes! Aperture Priority, often labelled “A” (for Aperture) or “Av” (for Aperture value) on Canon cameras, is where you choose the aperture, and your camera automatically selects the appropriate shutter speed for a correct exposure. You still control ISO.

Why Aperture? Aperture controls two main things:

- Depth of field: Or depth of sharpness as I like to call it. This is the range of distances in your image that appears acceptably sharp. A wide aperture (a small f-number like f/1.8 or f/2.8) gives you a shallow depth of field. This blurs the background beautifully (bokeh), isolating your subject – perfect for portraits. A narrow aperture (a large f-number like f/8 or f/16) gives you a deep depth of field, keeping much more of the scene sharp from front to back, ideal for landscapes or group photos.

- Light: A wider aperture lets in more light, which is incredibly useful in dim conditions where you don’t want to increase your ISO too much.

When to use it:

- Portraits: To blur backgrounds and make your subject pop.

- Landscapes: To ensure everything from a foreground flower to a distant mountain is sharp.

- Low light: To open up the lens and gather as much light as possible.

- Architectural photography. Like what I do.

This is a fantastic mode for creative control over focus and background blur.

Tip 4: Shutter Priority Mode (S or Tv): Control Your Motion (Freeze or Blur!)

Our fourth mode is Shutter Priority, usually marked “S” (for Shutter) or “Tv” (for Time value) on Canon cameras. In this mode, you choose the shutter speed, and your camera automatically selects the appropriate aperture for a correct exposure. You still control ISO.

Why Shutter Speed? Shutter speed primarily controls one thing: motion.

- Fast shutter speed (e.g., 1/500s or 1/1000s): This will freeze action. Think sports, kids running, or birds in flight. It’s also great for ensuring sharp handheld shots when worried about camera shake.

- Slow shutter speed (e.g., 1/30s, 1s, or even longer): This will blur motion. You can use it creatively to get silky smooth waterfalls, dramatic light trails from car headlights at night, or to convey movement in an action shot.

When to use it:

- Sports/Action: To perfectly freeze fast-moving subjects.

- Waterfalls/Rivers: To create that smooth, ethereal, misty look for moving water.

- Night photography (light trails): To capture the streaks of car lights or the movement of stars.

- Handheld in tricky light: To ensure a fast enough shutter speed to avoid your own camera shake, even if it means sacrificing some depth of field.

Shutter Priority is your go-to mode when controlling motion is your absolute main priority.

Tip 5: Manual Mode (M): The Ultimate Control Panel (Take Full Command)

Finally, we arrive at Manual Mode, marked with an “M”. This is where you take complete control over your exposure. You set the aperture, the shutter speed, and the ISO. Your camera’s built-in light meter will still give you a reading (usually a little scale in your viewfinder or on your screen) to help you achieve a correct exposure, but it won’t change anything automatically. And if your camera settings are way out the photo you get will be way out too. It is really all down to you.

When to use it:

- Consistent lighting: In a studio setting with controlled lights, or when ambient light isn’t changing. Once set, you can shoot repeatedly with the same exposure.

- Complex lighting: When the camera’s automatic meter might be fooled. For example, shooting a bright white subject on snow, or a very dark subject, where the camera might try to make it middle grey. You override the camera’s ‘guess’.

- Specific creative effects: When you need very precise control over both your depth of field and your motion blur simultaneously, such as for advanced long exposure photography or when intentionally over-exposing or under-exposing for artistic reasons.

- Learning: This is the most powerful learning tool. It forces you to truly understand the relationship between aperture, shutter speed, and ISO, invaluable for mastering photography. It might feel intimidating at first, but practicing in Manual mode is the fastest way to understand how all your settings work together.

- When you want to. Simple. If you want to use manual mode, go for it.

So, there you have it – a clear breakdown of your camera’s main shooting modes. Remember, there’s no single “best” mode; it’s about choosing the right tool for the job. Start with what’s comfortable, experiment with each one, and gradually take more control as your confidence grows. The more you understand these modes, the more command you’ll have over the final look of your images. Practice, practice, practice!

Note – other camera systems

Other camera manufacturers have similar modes with different names. But all of the above applies with any make of camera.

Here is something for you to do.

Learn manual mode. Yes really. Learn manual mode and tell me how you get on. Why should you do this? Because if you are serious about your photography there will be a time when you will need it. And if you do learn how to use manual mode and find yourself needing it don’t forget to thank me!

What if I use a phone to take my photos?

Great question Rick. Well all I do with my phone camera is use the default picture taking mode. I have never tried to find anything else. I have a camera for that after all.

So tell me dear listener – am I missing out here?

What do I do?

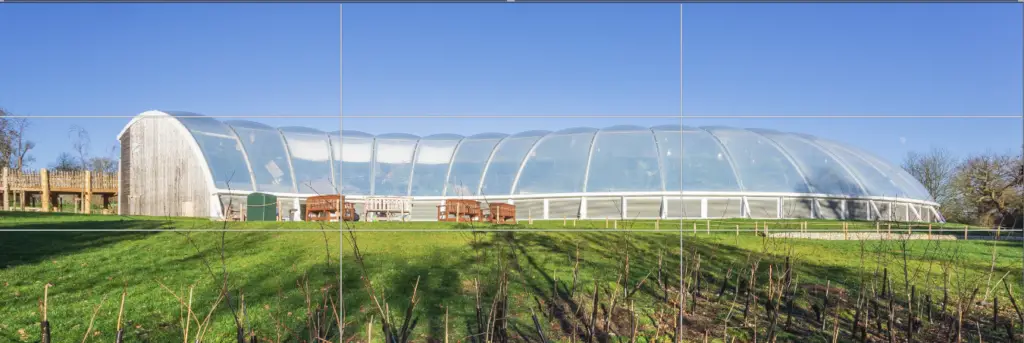

I am a professional architectural and real estate photographer. And I take all my photos with my camera on a tripod. Image quality, sharpness and the right depth of field (sorry depth of sharpness), so I use Av Mode, or aperture priority mode. I don’t really care what the shutter speed is, as what I am photographing is not moving. And I use the lowest ISO, which is 100. This is the ISO that my camera was designed to be used with. Change the ISO and you are digitally amplifying the signal. I would rather not do that.

I use P when I can’t be bothered doing anything else, which is when I am wandering around aimlessly and can’t be bothered thinking about camera settings. This is never on a commercial shoot mind. It is when I have free time to play, or I am on holiday.

It could be called can’t be bothered mode!

And I use Shutter priority when I need to, which is not often.

And I use manual mode when I need to or want to.

My approach boils down to meticulous control of everything:

- AV Mode all the way: I set my aperture for maximum sharpness (the lens’s sweet spot, often f/8), my ISO to the lowest possible (ISO 100 on my Canon 6D for maximum quality), and then the shutter speed is what it is. And yes it is that simple. This gives me ultra-consistent results.

- Precision focusing: I manually select my focus point for every shot, ensuring critical sharpness on the most important elements of a scene. I use back-button focus, which separates focus from exposure and taking the photo.

- Vibration elimination: I always use the built-in self-timer (2 or 10-second delay) to avoid any subtle vibrations caused by touching the camera.

- Lens choices: I pick the right lens for the job, understanding its characteristics, and always use a lens hood to maintain contrast and clarity.

This isn’t just theory; it’s the practical application of taking full control of my gear to ensure every image I deliver is crystal clear, professional, and reflects my precise vision.

Final Takeaways and Summary for Mastering Your Camera Modes

Understanding your camera’s modes is crucial for creative control. Each mode offers a different level of automation and flexibility:

- Auto: For quick, simple snapshots.

- Program (P): More control than Auto, with the ability to shift aperture/shutter combinations.

- Aperture Priority (A/Av): Control image quality and depth of field.

- Shutter Priority (S/Tv): Control motion (freeze or blur).

- Manual (M): Full control over all exposure settings.

Experiment with each mode. Practice makes perfect, transforming your photography technique to deliver professional results and capture your vision every time.

Host: Find show notes, links, and a summary at [Your Website Address Here] (search Episode 211).

- SEO Keywords for this Episode’s Blog Post: Camera Modes Explained, Photography Camera Settings, Auto Mode, Aperture Priority Mode, Shutter Priority Mode, Manual Mode, DSLR Modes, Mirrorless Camera Modes, Camera Dial Explained, Photography Basics, Learn Camera Settings, Beginner Photography Modes, Creative Camera Control, Depth of Field Control, Motion Blur Control, Exposure Control, Camera Settings Guide, Photography Tips, How To Use Camera Modes.

Some thoughts from the last episode

All I wanna say about the last episode, your aim with every photo is to get the sharpest photo you can, and that will make your photos stand out from everybody else other than professional photographers.

Next Episode

Next week: Episode 212: Creative Use of Depth of Field: Blurry Backgrounds, Sharp Subjects. We’ll dive deeper into using aperture to control what’s sharp and what’s gloriously blurred in your photos. Subscribe so you don’t miss it!

Get an email from me.

Want a weekly email from me? Fill in the box on any of my websites. Every Friday, you’ll read my photography thoughts.

Ask me a question

Have a question or want to say hi? Email sales@rickmcevoyphotography.co.uk, visit the podcast website, or text me from the podcast feed. It’s always lovely to hear from you, my dear listeners.

Subscribe and Never Miss an Episode!

Enjoying the podcast? Subscribe now on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you listen. It ensures you get every new episode and helps us reach more photographers! Don’t delay, subscribe today!

This episode was brought to you by a cheese and pickle sandwich and a popular carbonated soft drink with zero sugar in it, which I consumed it before settling in my homemade, acoustically cushioned recording emporium.

I’ve been Rick McEvoy. Thanks again for listening to my small but perfectly formed podcast and for giving me 27 minutes of your valuable time. I reckon this episode will be about 25 minutes long after editing out the mistakes and bad stuff.

Thanks for listening

Take care and stay safe.

Cheers from me, Rick

Want to know more?

Head over to the Start page on the Photography Explained Podcast website to find out more.

And here is the list of episodes published to date – you can listen to any episode straight from this page which is nice.

Let me know if there is a photography thing that you want me to explain and I will add it to my list. Just head over to the This is my list of things to explain page of this website to see what is on there already.

Let me send you stuff

I send out a weekly email to my subscribers. It is my take on one photography thing, plus what I have been writing and talking about. Just fill in the box and you can get my weekly photographic musings straight to your inbox. Which is nice.

And finally a little bit about me

Finally, yes this paragraph is all about me – check out my Rick McEvoy Photography website to find out more about me and my architectural, construction, real estate and travel photography work. I also write about general photography stuff, all in plain English without the irrelevant detail.

Thank you

Thanks for listening to my podcast (if you did) and reading this blog post (which I assume you have done as you are reading this).

Cheers from me Rick